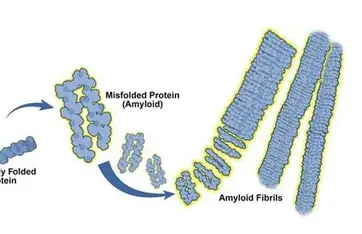

Overview: AL (light-chain) amyloidosis is a rare blood disorder in which a small clone of plasma cells overproduces misfolded immunoglobulin light chains that deposit as amyloid fibrils in organs (heart, kidneys, liver, nerves, etc.). Symptoms depend on the organs affected and are often nonspecific (heart failure, nephrotic syndrome, neuropathy, etc.). Because signs mimic other diseases, diagnosis is often delayed.

Advances in disease understanding: Recent studies are illuminating the molecular and immunologic features of AL amyloidosis. For example, single-cell RNA sequencing of patients’ bone marrow shows an unusually inflammatory environment – with increased TNF-α and interferon signaling in immune cells – and a distinct population of non-malignant plasma cells (expressing CRIP1) that expand alongside the malignant clone. The clonal AL plasma cells themselves overexpress genes related to protein folding and proteostasis, consistent with stress from misfolded light chains. These findings highlight how AL differs from multiple myeloma and suggest new targets for therapy (e.g. modulating immune responses to amyloid). Other insights include genetic biases (most AL clones use λ light chains and certain V–J gene segments prone to misfolding). Importantly, large database studies (e.g. UK Biobank) have identified blood proteins that predict amyloid risk years before symptoms – raising the possibility of screening at-risk individuals much earlierarci.org. Researchers have also refined prognostic staging: the latest models split patients with advanced cardiac involvement into Stage IIIa, IIIb and a newly defined Stage IIIc. Stage IIIc (defined by very high NT-proBNP, troponin, and abnormal strain) identifies a small ultra-high-risk group with median survival <1 year. Recognizing Stage IIIc patients helps tailor aggressive therapy or trial enrollment.

Diagnostic advances: Confirming AL amyloidosis still relies on tissue biopsy. A biopsy (e.g. fat pad, kidney, or heart) stained with Congo red (showing apple-green birefringence) is required for diagnosis. Modern protocols emphasize typing the amyloid fibril by mass spectrometry, the gold standard to prove it is immunoglobulin light chain–derived. Cardiac evaluation now often uses sensitive biomarkers (NT-proBNP, high-sensitivity troponin) plus imaging. Novel tools are emerging to catch disease earlier: screening high-risk MGUS patients (monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance) with serial biomarkers has proven feasible. In one study of intermediate/high-risk MGUS, proactive biomarker monitoring allowed detection of pre-symptomatic AL and early treatment – which translated into improved organ recovery. Likewise, artificial intelligence is helping. Investigators developed a deep-learning model (a “vision transformer”) to analyze cardiac MRI images; it could distinguish cardiac amyloidosis from hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with ~84% accuracy. This tool might reduce the long diagnostic delays (often 2–3 years) by alerting radiologists to subtle amyloid findings. Other innovative diagnostics under study include urine tests (e.g. detecting light-chain oligomers in extracellular vesicles) and more sensitive cardiac imaging. Despite these advances, delayed diagnosis remains a major challenge – patient and physician education and streamlined referral pathways are ongoing needs.

Treatment advances: The backbone of AL therapy remains plasma-cell–directed chemotherapy, borrowing from multiple myeloma regimens. In 2021 the FDA approved daratumumab (a CD38 antibody) for AL amyloidosis; it is now commonly given with bortezomib, cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone (so-called D-VCd) as first-line treatment. This daratumumab-based quadruplet has produced unprecedented responses. In the recent AQUARIUS trial, >90% of newly diagnosed AL patients (even those with cardiac involvement) responded hematologically to D-VCd, with many reporting improved function and quality of life. The goal of therapy is a very good partial response or better (≥VGPR), which strongly correlates with organ improvement. Patients who fail initial therapy have several options: pomalidomide, lenalidomide or alkylators, and – for those eligible – autologous stem cell transplant.

- Targeted therapies: Genetic features can guide treatment. About half of AL patients harbor a chromosomal translocation t(11;14); for these, venetoclax (a BCL-2 inhibitor) has shown remarkable activity. Early trials report very high response rates (often complete responses) and even organ improvements in t(11;14) cases. For all relapsed/refractory patients, novel immune therapies are on the horizon. Bispecific antibodies that bring T cells to plasma cells (usually by binding BCMA on the plasma cell and CD3 on T cells) are being tested. For example, the bispecific “etentamig” (ABBV-383) has shown rapid, deep remissions in early trials. Multiple other BCMA-targeting bispecifics are now in trials (linvoseltamab, elranatamab, teclistamab, etc.).

- CAR T-cell therapy: Remarkable early results have been seen with anti-BCMA CAR T cells in AL. A phase 1 study (Nexicart-2) treated heavily pretreated patients with BCMA-directed CAR T (NXC-201). All patients had rapid, deep hematologic responses: 70% had complete remission by day 7, and the rest were MRD-negative in marrow. In the first ~20 patients across trials, 19/20 normalized their serum light chains within two weeks, and 14/16 evaluable patients achieved MRD-negative marrow by one month. Importantly, organ function (heart/kidney) also improved in many cases, and toxicities have been manageable (no severe CRS or neurotoxicity reported so far). These striking outcomes suggest CAR T could become a “one-time” therapy for relapsed AL. Larger trials are underway to confirm safety and durability.

- Anti-amyloid (fibril-clearing) therapies: A major unmet need is removing deposited amyloid. Several monoclonal antibodies aim to do this, but results have been mixed. Birtamimab (formerly NEOD001) binds light-chain fibrils. Its Phase 3 VITAL trial was stopped early for futility (no benefit in the overall cohort), but a post-hoc analysis showed a survival gain in the sickest patients (Mayo Stage IV). This has led to a follow-up trial (AFFIRM-AL) focusing on stage IV patients. Anselamimab (formerly CAEL-101, from Alexion) also targets AL deposits; its CARES Phase 3 trial recently failed to meet its primary survival endpoint. (The drug was well-tolerated, and some subgroup benefits are being explored.) In contrast, CAEL-101 (another anti–amyloid antibody from Prothena) is actively in two Phase 3 studies (one in Mayo IIIa, one in IIIb) that test whether it can improve survival and organ function when added to chemotherapy. In preclinical models, CAEL-101 and similar antibodies appear to trigger macrophages to clear amyloid. These trials should report in the next 1–2 years.

- Supportive care improvements: Though not new drugs, better management of organ complications also advances care. For example, cardiologists are applying new imaging criteria and cautiously using heart-failure drugs (midodrine, etc.) in AL patients; nephrologists use ACE inhibitors only if tolerated. Multidisciplinary clinics (cardio-renal-hematology teams) are increasingly common. Importantly, consensus guidelines now stress aggressive workup of suspected cases (e.g. testing all unexplained heart-failure or nephrotic patients for AL) to catch disease sooner.

Summary: AL amyloidosis research in the past 1–2 years has brought real hope. A combination of earlier detection (via screening biomarkers and AI imaging), improved staging, and new therapies is changing the outlook. Daratumumab-based induction is now standard, and novel drugs like venetoclax are extending response. Cutting-edge approaches such as BCMA CAR T-cells and bispecific T‑cell engagers are yielding unprecedented remissions. Trials of amyloid-clearing antibodies (CAEL-101, etc.) are finally testing the long-sought dream of reversing organ damage. Altogether, these advances – drawn from recent peer-reviewed studies and expert reports – promise more accurate diagnosis and more effective, individualized treatment for patients with this challenging disease